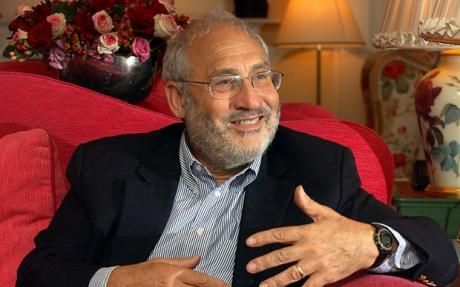

THE TELEGRAPH: In an exclusive extract from his new book, Freefall, the former World Bank chief economist, reveals why banks should be split up and why the West must cut consumption.

In the Great Recession that began in 2008, millions of people in America and all over the world lost their homes and jobs. Many more suffered the anxiety and fear of doing so, and almost anyone who put away money for retirement or a child's education saw those investments dwindle to a fraction of their value.

A crisis that began in America soon turned global, as tens of millions lost their jobs worldwide – 20m in China alone – and tens of millions fell into poverty.

This is not the way things were supposed to be. Modern economics, with its faith in free markets and globalisation, had promised prosperity for all. The much-touted New Economy – the amazing innovations that marked the latter half of the 20th century, including deregulation and financial engineering – was supposed to enable better risk management, bringing with it the end of the business cycle. If the combination of the New Economy and modern economics had not eliminated economic fluctuations, at least it was taming them. Or so we were told.

The Great Recession – clearly the worst downturn since the Great Depression 75 years earlier – has shattered these illusions. It is forcing us to rethink long-cherished views.

For a quarter century, certain free-market doctrines have prevailed: free and unfettered markets are efficient; if they make mistakes, they quickly correct them. The best government is a small government, and regulation only impedes innovation. Central banks should be independent and only focus on keeping inflation low.

Today, even the high priest of that ideology, Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board during the period in which these views prevailed, has admitted that there was a flaw in this reasoning – but his confession came too late for the many who have suffered as a consequence.

In time, every crisis ends. But no crisis, especially one of this severity, passes without leaving a legacy. The legacy of 2008 will include new perspectives on the long-standing conflict over the kind of economic system most likely to deliver the greatest benefit.

I believe that markets lie at the heart of every successful economy but that markets do not work well on their own. In this sense, I'm in the tradition of the celebrated British economist John Maynard Keynes, whose influence towers over the study of modern economics.

Government needs to play a role, and not just in rescuing the economy when markets fail and in regulating markets to prevent the kinds of failures we have just experienced. Economies need a balance between the role of markets and the role of government – with important contributions by non-market and non-governmental institutions. In the last 25 years, America lost that balance, and it pushed its unbalanced perspective on countries around the world.

The current crisis has uncovered fundamental flaws in the capitalist system, or at least the peculiar version of capitalism that emerged in the latter part of the 20th century in the US (sometimes called American-style capitalism). It is not just a matter of flawed individuals or specific mistakes, nor is it a matter of fixing a few minor problems or tweaking a few policies.

It has been hard to see these flaws because we Americans wanted so much to believe in our economic system. "Our team" had done so much better than our arch enemy, the Soviet bloc. >>> | Saturday, January 23, 2010